Once Upon a Time...in Buenos Aires

Beginning

Depending on whether I get any more consulting jobs, this might be my last international vacation. The freelance work I've done since I retired has not been necessary to my financial survival, but, besides enjoying those assignments, it's provided me economic elbow room for the occasional luxury, like a nice overseas vacation. Because consulting is a tenuous source of income and because during my golden years I no longer consider traveling essential, which I did during the years I worked full-time, I don't know if there will be other big trips after this one.

This past August, when starting to plan for a trip, I therefore gave extra thought as to its destination. Although I’d happily have gone back to Seoul, a city I’ve visited ten times, or Hong Kong, seven times, and considered both as easy options, I really needed to see some place new to me. East Asian cultures are my favorite, but Latin ones are second, and I was leaning strongly in this direction, thus narrowing the possibilities to Panama, Colombia, or Argentina. The latter was my choice earlier this century, but for reasons I discuss at the end of this webpage I changed my mind and instead returned to Korea. But now...hmmm. Buenos Aires is a big city, I thought, the Paris of South America, and after nineteen laid-back months in Tucson I’ve wanted to spend time in a high-energy location. Plus, for these many years I have considered Argentina unfinished business, which rattles my Type A personality.

The code for the international airport in Buenos Aires is EZE, which is short for Ezeiza. The Ezeizas were wealthy landowners in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Argentina. Upon the death of the family's patriarch, the son-in-law donated a large tract of land in Greater Buenos Aires to the Buenos Aires Western Railway. A town sprung up around the tracks and was named Ezeiza Partido in the father's honor. In 1945, the government of Juan Perón cleared the way for the airport's construction on the north end of town; it started operations in 1949 as the third largest airport in the world. The airport's official name is Aeropuerto Internacional Ministro Pistarini, after Juan Pistarini, the Minister of Public Works in the Perón administration.

Cashing in 140,000 miles from my Delta frequent flyer account for an economy class seat, I made EZE my destination, flying first out of PHX and ATL. The flight from Phoenix was on an Airbus A321, fresh and modern, at least as much as an airplane can be; Atlanta to Buenos Aires was on an old, worn-out Boeing 767-400ER, cramped, with tiny, poorly calibrated screens in the seatbacks for watching films or tracking the flight. The first leg of the trip lasted two and a half hours; the second, about 4600 miles, nine and a half hours.

Delta 101 landed in Buenos Aires twenty minutes ahead of schedule, at 09:00, Wednesday, 4 December 2019. (On this webpage I will be designating time with the international standard of a twenty-four-hour clock. This saves me from repeating “a.m.” or “p.m.” or saying “in the morning” or “that afternoon” over and over.) Passport control took only forty-five minutes, nowhere near as long as I expected, read about, and feared. One source said be prepared for two hours, maybe even three. I power-walked from the airplane to passport control, whizzing by almost everyone who disembarked before me. Still, several international flights arrived into the airport at about the same time and more than fifty people were queued ahead of me after my sprint. But in the visitors’ section authorities manned five stations to keep the lines progressing with admirable efficiency.

Comments on Trip Advisor were unanimous in admonishing international visitors to exchange money at the Banco de la Nación Argentina at the airport, Terminal A, which is also the location of customs, so as you pass through the exit doors, there you are. The Banco is tucked around the corner from Starbucks. I exchanged the daily maximum, US$100, and got AR$5775 in return. (Argentina’s currency is called the peso, but its symbol is the familiar dollar sign; I'm putting a US or AR in front of the symbol so it's clear as to which country's currency I'm referring.) Selling pesos, at the end of the trip, meant AR$62 for US$1. I easily found the Taxi EZE kiosk—another on-line admonishment—and paid AR$1550 with a credit card for a ride to the hotel.

It was overcast and seventy degrees when I got in the cab at about 10:15. With light traffic, the ride downtown took thirty minutes.

This past August, when starting to plan for a trip, I therefore gave extra thought as to its destination. Although I’d happily have gone back to Seoul, a city I’ve visited ten times, or Hong Kong, seven times, and considered both as easy options, I really needed to see some place new to me. East Asian cultures are my favorite, but Latin ones are second, and I was leaning strongly in this direction, thus narrowing the possibilities to Panama, Colombia, or Argentina. The latter was my choice earlier this century, but for reasons I discuss at the end of this webpage I changed my mind and instead returned to Korea. But now...hmmm. Buenos Aires is a big city, I thought, the Paris of South America, and after nineteen laid-back months in Tucson I’ve wanted to spend time in a high-energy location. Plus, for these many years I have considered Argentina unfinished business, which rattles my Type A personality.

The code for the international airport in Buenos Aires is EZE, which is short for Ezeiza. The Ezeizas were wealthy landowners in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Argentina. Upon the death of the family's patriarch, the son-in-law donated a large tract of land in Greater Buenos Aires to the Buenos Aires Western Railway. A town sprung up around the tracks and was named Ezeiza Partido in the father's honor. In 1945, the government of Juan Perón cleared the way for the airport's construction on the north end of town; it started operations in 1949 as the third largest airport in the world. The airport's official name is Aeropuerto Internacional Ministro Pistarini, after Juan Pistarini, the Minister of Public Works in the Perón administration.

Cashing in 140,000 miles from my Delta frequent flyer account for an economy class seat, I made EZE my destination, flying first out of PHX and ATL. The flight from Phoenix was on an Airbus A321, fresh and modern, at least as much as an airplane can be; Atlanta to Buenos Aires was on an old, worn-out Boeing 767-400ER, cramped, with tiny, poorly calibrated screens in the seatbacks for watching films or tracking the flight. The first leg of the trip lasted two and a half hours; the second, about 4600 miles, nine and a half hours.

Delta 101 landed in Buenos Aires twenty minutes ahead of schedule, at 09:00, Wednesday, 4 December 2019. (On this webpage I will be designating time with the international standard of a twenty-four-hour clock. This saves me from repeating “a.m.” or “p.m.” or saying “in the morning” or “that afternoon” over and over.) Passport control took only forty-five minutes, nowhere near as long as I expected, read about, and feared. One source said be prepared for two hours, maybe even three. I power-walked from the airplane to passport control, whizzing by almost everyone who disembarked before me. Still, several international flights arrived into the airport at about the same time and more than fifty people were queued ahead of me after my sprint. But in the visitors’ section authorities manned five stations to keep the lines progressing with admirable efficiency.

Comments on Trip Advisor were unanimous in admonishing international visitors to exchange money at the Banco de la Nación Argentina at the airport, Terminal A, which is also the location of customs, so as you pass through the exit doors, there you are. The Banco is tucked around the corner from Starbucks. I exchanged the daily maximum, US$100, and got AR$5775 in return. (Argentina’s currency is called the peso, but its symbol is the familiar dollar sign; I'm putting a US or AR in front of the symbol so it's clear as to which country's currency I'm referring.) Selling pesos, at the end of the trip, meant AR$62 for US$1. I easily found the Taxi EZE kiosk—another on-line admonishment—and paid AR$1550 with a credit card for a ride to the hotel.

It was overcast and seventy degrees when I got in the cab at about 10:15. With light traffic, the ride downtown took thirty minutes.

*A word about the format*

I've put together most of my previous vacation logs, hard copies and digital, by date, such that they read like journals. A few I’ve arranged by location. Others still, when I got lazy, I threw down a couple of introductory sentences and then posted the photos. So as not to keep repeating myself and to keep things interesting for me and I hope for the reader, I’ve ordered this webpage by topic, which is common in some guidebooks. Pardon me if I present too much detail, but that approach helps me remember everything better, and I believe a reader thinking about or preparing for a trip to Buenos Aires will find those specifics useful. Also, I’ve decided not to translate the names of the museums, streets, and the like into English, instead leaving them in Spanish, as these are their official names; you will have no trouble understanding their meaning.

I need to ask you a favor: I have read, read, and re-read the words on this page and have corrected bad grammar, poor style, and typographical errors dozens of times. If you find any proofreading snafus I've overlooked, then please contact me at rafedor@icloud.com so I can fix them. Thanks.

I need to ask you a favor: I have read, read, and re-read the words on this page and have corrected bad grammar, poor style, and typographical errors dozens of times. If you find any proofreading snafus I've overlooked, then please contact me at rafedor@icloud.com so I can fix them. Thanks.

Time and Weather

Time in Buenos Aires is UTC –3, which is four hours ahead of Mountain Standard Time. UTC stands for Coordinated Universal Time, synonymous with Greenwich Mean Time.

Buenos Aires, all of Argentina, and nearly all of South America are in the southern hemisphere. (Please note: three reliable English-language resources say the “s” in “southern” and the “h” in hemisphere” are lower-case letters.) Because of this sub-equatorial location, seasons are opposite of those in North American and European countries. Spring was ending and summer about to begin for the Argentines, and I had beautiful weather during my stay: no rain and the sun shone every day but one, when it was mostly cloudy. The air temperature, in degrees Fahrenheit, in Buenos Aires for my trip:

Date 4 Dec 5 Dec 6 Dec 7 Dec 8 Dec 9 Dec 10 Dec 11 Dec 12 Dec

High 76 78 80 74 86 88 100 94 80

Low 57 54 65 60 66 70 72 71 75

In the evenings it got dark outside at about 20:15 and light in the morning at about 05:20.

Buenos Aires, all of Argentina, and nearly all of South America are in the southern hemisphere. (Please note: three reliable English-language resources say the “s” in “southern” and the “h” in hemisphere” are lower-case letters.) Because of this sub-equatorial location, seasons are opposite of those in North American and European countries. Spring was ending and summer about to begin for the Argentines, and I had beautiful weather during my stay: no rain and the sun shone every day but one, when it was mostly cloudy. The air temperature, in degrees Fahrenheit, in Buenos Aires for my trip:

Date 4 Dec 5 Dec 6 Dec 7 Dec 8 Dec 9 Dec 10 Dec 11 Dec 12 Dec

High 76 78 80 74 86 88 100 94 80

Low 57 54 65 60 66 70 72 71 75

In the evenings it got dark outside at about 20:15 and light in the morning at about 05:20.

Hotel

As with all big cities, Buenos Aires has a wide range of hotels the traveler can choose from. Being a retiree on a fixed income I had to be practical in selecting a place to stay, deciding finally on the economical Holiday Inn Express in Puerto Madero. The location was fine, but I doubt it was originally a Holiday Inn property—the building’s interior was old, tired, and needed updating. My small room was on the second floor—third by U.S. naming conventions—but despite the hotel being on a busy street, traffic noise was no issue. Unlike Holiday Inn Express rooms in the U.S., this one had no refrigerator or microwave oven. But the bed was comfortable with clean, fresh sheets and a variety of pillows. And the tiny bathroom had nice, big, fluffy towels. The wide-screen television had access to sixty-four channels, all but one of which were Spanish-language or dubbed in Spanish. On the top floor, the fourteenth, was the hotel’s fitness center, slightly larger than average but with the typical stationary equipment: two treadmills, a bike, and an elliptical machine. It did, however, have enough extra floor space and a couple of mats such that I was able to work out with the FitOn app on my iPad, so I missed no exercise days. I will say the hotel staff was helpful: maintenance repaired the non-functioning deadlock on my room’s door the same day I reported it; their IT people, within minutes of my calling the front desk, fixed the problem of the entire second floor losing its internet connection; and the front desk folks happily answered my questions about the city. Next to the hotel was a bakery and a Lotería de la Ciudad, which is a microversion of a 7–11 convenience store. A subway stop was a fifteen-minute walk, turning right as you left the hotel's main entrance.

People

I’ll try to not get too numerical in this section, but some numbers, I’m afraid, are difficult to avoid.

Argentina has a population of forty-five million; greater Buenos Aires, fifteen million; Buenos Aires-proper, three million. Argentina is very much a country of immigrants, with most coming from two western European countries: 45% from Italy, 45% from Spain. Although back in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries a third of the country’s population was black, most brought as slaves from Senegal or descended from Senegalese slaves. Today the black population in the country and in Buenos Aires is no more than 1%. What happened? Several theories abound, probably each with a bit of truth: cholera and yellow fever epidemics in the mid- to late 1800s; a deadly war with Paraguay in 1865, disproportionately fought by blacks; systematic genocide; mass emigration to countries friendlier to them, such as Brazil and Uruguay. Enough said on that subject, because it's undoubtedly incendiary and sensitive.

What I can tell you without controversy is that almost no Argentines have blonde hair; most have dark complexions and black hair. On average, Argentines seem tall. I have no data to substantiate this—it’s purely anecdotal.

Inhabitants of Buenos Aires are known as porteños, which means people of the port, because of the city’s location on the enormous Rio de la Plata. By reputation porteños are at once egocentric and self-critical, outgoing but sensitive. They also tend to be night owls, which accounts for dinner starting at 22:30 and sometimes not until midnight. (Oh, my aching reflux.) A collective mentality imbues the population, not necessarily in a political sense, but in the way the locals value living life to its fullest, placing a premium on fun and pleasure. At least that’s what I’ve read and was told. I don’t know if that attitude explains the number of people of all ages with tattoos, but I’ve never seen such a concentration of inked humans. And far too many young Argentine women have nose piercings.

And speaking of women, I couldn’t help but notice they emphasize their upper torsos rather than their hips. Lots of chesty señoritas and señoras here. And maybe because it’s almost summer, but most under-the-blouse supports were barely there. Things appear natural but I can’t say for sure. But those tattoos. Many Buenos Aires women are attractive, but they lose their appeal because of their abundance of tattoos. What were they thinking? Also, quite a few women were wearing platform shoes and looked like they could hardly balance—pretty silly.

Argentina has a population of forty-five million; greater Buenos Aires, fifteen million; Buenos Aires-proper, three million. Argentina is very much a country of immigrants, with most coming from two western European countries: 45% from Italy, 45% from Spain. Although back in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries a third of the country’s population was black, most brought as slaves from Senegal or descended from Senegalese slaves. Today the black population in the country and in Buenos Aires is no more than 1%. What happened? Several theories abound, probably each with a bit of truth: cholera and yellow fever epidemics in the mid- to late 1800s; a deadly war with Paraguay in 1865, disproportionately fought by blacks; systematic genocide; mass emigration to countries friendlier to them, such as Brazil and Uruguay. Enough said on that subject, because it's undoubtedly incendiary and sensitive.

What I can tell you without controversy is that almost no Argentines have blonde hair; most have dark complexions and black hair. On average, Argentines seem tall. I have no data to substantiate this—it’s purely anecdotal.

Inhabitants of Buenos Aires are known as porteños, which means people of the port, because of the city’s location on the enormous Rio de la Plata. By reputation porteños are at once egocentric and self-critical, outgoing but sensitive. They also tend to be night owls, which accounts for dinner starting at 22:30 and sometimes not until midnight. (Oh, my aching reflux.) A collective mentality imbues the population, not necessarily in a political sense, but in the way the locals value living life to its fullest, placing a premium on fun and pleasure. At least that’s what I’ve read and was told. I don’t know if that attitude explains the number of people of all ages with tattoos, but I’ve never seen such a concentration of inked humans. And far too many young Argentine women have nose piercings.

And speaking of women, I couldn’t help but notice they emphasize their upper torsos rather than their hips. Lots of chesty señoritas and señoras here. And maybe because it’s almost summer, but most under-the-blouse supports were barely there. Things appear natural but I can’t say for sure. But those tattoos. Many Buenos Aires women are attractive, but they lose their appeal because of their abundance of tattoos. What were they thinking? Also, quite a few women were wearing platform shoes and looked like they could hardly balance—pretty silly.

HIstory

I’m not going to write a detailed history of Argentina or Buenos Aires; I’m barely going to present a superficial one. Writing and reading history are a paradox. We all know the cliché that the winners write history, and we also all know that partly because of who’s doing the writing we have to approach studying history with a degree of caution. Added to that is unless you’re reading a highly skilled writer who is discussing a particular—and peculiar—topic from the past, history can be boring. Because by its nature it includes a lot of people names, place names, and dates, the majority of which the you presumably don’t know or else he wouldn’t be reading the work, it’s not always easy for those the details to stick in your memory, adding to the dryness and sometimes creating a sense of frustration.

Here, then, are just a couple of tidbits about the region, spanning centuries in a few sentences, I hope interesting, with others sprinkled in throughout the other sections on the webpage.

The Spanish founded Argentina in 1536, when Pedro Mendoza and his explorers were looking for sources of silver. The name Argentina comes from the Latin, argentum, which means silver. Sad to say, that group didn’t stay for long, for after starving and resorting to cannibalism they fled to Asunción, in Paraguay. A conquistador named Juan de Garay was more successful in 1580; he came, he stayed, and he named the settlement Ciudad de la Trinidad and called what was to become the port, Puerto de Santa Maria del Buen Ayre. Buenos Aires translates from the Spanish to English as fair winds or good airs. Long a Spanish colony, Argentina took a big step toward independence on 25 May 1810, when it assumed responsibility for governing Buenos Aires. This day is celebrated as a national holiday as El Día de la Revolución de Mayo. Argentina finally became independent in 1816. The government abolished slavery in 1818. Its history almost to the present day has been tumultuous, with regular military dictatorships and violent overthrows of sitting administrations. Jumping ahead 174 years, a tragedy from without occurred in 1992, when terrorists, likely Iranian, blew up the Israeli embassy in Buenos Aires, killing twenty-nine. In the process, the suicide bomber and his pick-up truck destroyed a Catholic church and nearby school. As a memorial, Israel planted twenty-nine trees on the property and has left the silhouette of the embassy on the adjacent building.

Here, then, are just a couple of tidbits about the region, spanning centuries in a few sentences, I hope interesting, with others sprinkled in throughout the other sections on the webpage.

The Spanish founded Argentina in 1536, when Pedro Mendoza and his explorers were looking for sources of silver. The name Argentina comes from the Latin, argentum, which means silver. Sad to say, that group didn’t stay for long, for after starving and resorting to cannibalism they fled to Asunción, in Paraguay. A conquistador named Juan de Garay was more successful in 1580; he came, he stayed, and he named the settlement Ciudad de la Trinidad and called what was to become the port, Puerto de Santa Maria del Buen Ayre. Buenos Aires translates from the Spanish to English as fair winds or good airs. Long a Spanish colony, Argentina took a big step toward independence on 25 May 1810, when it assumed responsibility for governing Buenos Aires. This day is celebrated as a national holiday as El Día de la Revolución de Mayo. Argentina finally became independent in 1816. The government abolished slavery in 1818. Its history almost to the present day has been tumultuous, with regular military dictatorships and violent overthrows of sitting administrations. Jumping ahead 174 years, a tragedy from without occurred in 1992, when terrorists, likely Iranian, blew up the Israeli embassy in Buenos Aires, killing twenty-nine. In the process, the suicide bomber and his pick-up truck destroyed a Catholic church and nearby school. As a memorial, Israel planted twenty-nine trees on the property and has left the silhouette of the embassy on the adjacent building.

Politics and Economics

I won't comment on the politics of Argentina for several reasons: I don’t know enough about it, and I'm not going to pretend I do; it’s a complex and explosive topic, figuratively and sometimes literally; and I am a guest in their country, not a citizen, so it’s none of my beeswax. Given that, here is some objective information about the local government.

Center-right Mauricio Macri was Argentina’s president when I arrived; center-left Alberto Fernandez became president on 10 December, two days before I left. Casa Rosada (the Pink House) is the seat of the Argentine national government and from whose balconies Eva Perón inspired and infuriated the nation. It's located in Plaza de Mayo and is where Mr. Fernandez and other federal officials have their office. On inauguration day I made the short walk from the hotel to the plaza. As you’d expect the area was guarded by a lot of security, with entry points blocked closest to Casa Rosada. In the plaza itself were many people, mostly young, of course, with posters and banners, presumably for and against the new president and his political party and other philosophies on which they chose to voice their opinions, whether or not anyone wanted to hear them.

Like most of South America, Argentina has struggled with inflation, with the rate averaging 196% from 1944 to this year. This past November it was a 51%. The Argentine peso has lost two-thirds of its value since last year. The poverty rate is unfortunately high, also, with 2019's being the highest in a decade, averaging around 40%. Not specific to any neighborhood, as I walked I occasionally saw homeless people sleeping on old, dirty mattresses on sidewalks up against buildings. (If you’d like to compare Argentina's poverty rate to that in other countries, then it’s about 11% in the U.S., 10% in Canada, 42% in Mexico, 19% in Germany, 46% in Kenya, and 12% in Saudi Arabia. China’s data on this are unreliable, as I suspect all these numbers are to some extent.)

Education in Argentina is free, from kindergarten through college, but college is an additional nine years. Because of that time commitment, some people choose to pay for private university, which is a traditional four-year program.

Center-right Mauricio Macri was Argentina’s president when I arrived; center-left Alberto Fernandez became president on 10 December, two days before I left. Casa Rosada (the Pink House) is the seat of the Argentine national government and from whose balconies Eva Perón inspired and infuriated the nation. It's located in Plaza de Mayo and is where Mr. Fernandez and other federal officials have their office. On inauguration day I made the short walk from the hotel to the plaza. As you’d expect the area was guarded by a lot of security, with entry points blocked closest to Casa Rosada. In the plaza itself were many people, mostly young, of course, with posters and banners, presumably for and against the new president and his political party and other philosophies on which they chose to voice their opinions, whether or not anyone wanted to hear them.

Like most of South America, Argentina has struggled with inflation, with the rate averaging 196% from 1944 to this year. This past November it was a 51%. The Argentine peso has lost two-thirds of its value since last year. The poverty rate is unfortunately high, also, with 2019's being the highest in a decade, averaging around 40%. Not specific to any neighborhood, as I walked I occasionally saw homeless people sleeping on old, dirty mattresses on sidewalks up against buildings. (If you’d like to compare Argentina's poverty rate to that in other countries, then it’s about 11% in the U.S., 10% in Canada, 42% in Mexico, 19% in Germany, 46% in Kenya, and 12% in Saudi Arabia. China’s data on this are unreliable, as I suspect all these numbers are to some extent.)

Education in Argentina is free, from kindergarten through college, but college is an additional nine years. Because of that time commitment, some people choose to pay for private university, which is a traditional four-year program.

Water and Food

I am not arranging these sections in order of importance to me, for if I did, this one would be at the end. I'm putting these in a sequence that I think most readers will find useful.

Considering that I have a degree in food engineering and worked directly in the food industry from thirty-one years and indirectly for five and a half it might seem incongruous for me to derive so little pleasure from eating that, with a couple of exceptions, I do it just to survive. Eat to live, that's me. I know two other people only who share my philosophy, and we, the oppressed and misunderstood, are up against the rest of the world, for whom eating is a top priority. Other than for a truly great pizza, which is difficult to find, I wouldn't go out of my way to have a regular meal in a restaurant. I have eaten in restaurants of all kinds all over the world and virtually none has been worth the money to me. Yes, I know I'm missing out on part of a particular location's culture, but, I don't care; I more than make up for the loss in other ways.

Having said that, here's some information about the local water and food.

Online sources said tap water in Buenos Aires is safe to drink. I asked the cabbie who drove me from the airport about this, and in broken English he said brushing teeth with the tap water, yes, drinking, no, as the city water came from the Rio de la Plata, a dirty river, and, though probably microbiologically safe, it tasted chemically. Being cautious, I followed his advice and had no problems.

From what I read and given the high percentage of Argentines with Italian heritage and on the basis of the types of restaurants I saw throughout the city, the locals love pizza. Good for them. It might sound extreme but in continuing my lifelong quest to find the world's greatest pizza, I tried the Buenos Aires version three times. And the city has a world-renowned pizza place: Güerrin Pizza, established 1932. Contrary to what my references warned, it wasn’t too crowded when I got to Güerrin at noon.

My choice for pizza topping is, first, sausage; second, pepperoni; third, sausage and pepperoni; and last, cheese. Strange as it seemed to me, Güerrin—and seemingly all of Buenos Aires—does not offer sausage or pepperoni as options, so cheese—"muzzarella"—it was. I ordered chica size, about twelve-inch diameter, and had no trouble finishing it, even though I didn't care for it. The sauce tasted more appropriate for pasta than for pizza, and the medium-thick crust had some body to it but its flavor was so-so, lacking in character. As with the other two pizzas I had in town, Güerrin's had a lot of cheese, which for me isn’t what pizza is about. Great pizza starts with a great crust followed by great sauce; after that, everything else is just a topping that has nothing to do with the artistry of a pizza. Bottom line for Güerrin: it was a good experience but the pizza was like a grilled cheese sandwich. The bill was AR$500.

Of course Argentina is known for its beef, and I did have a quality steak at a high-end restaurant called El Mirasol, which was on the Puerto Madero riverfront in a renovated group of buildings, convenient to my hotel. The area has several restaurants—almost nothing but restaurants—ranging from fast-food to elegant. El Mirasol, which has been around since 1967, is fancy inside and provides friendly, attentive service. I wanted filet mignon, but it was offered in one size only, 600 grams, about 1.3 pounds—too much for me. The waiter recommended sirloin steak, which clocks in at 300 grams, or about 10.5 ounces—still pretty big, but I was starving, so I ordered that, medium, with boiled potatoes. Hey, my stomach is still Midwestern—plus they didn’t have baked potatoes.

I will say the beef and dessert were outstanding and cost a little less than US$29, including tip. I have to thank the Puerto Rican couple I met on the ship to Uruguay for recommending El Mirasol.

Still not done, the locals love chocolate and ice cream. I tried them both, separately and together a couple of times during my stay and they were flavorful. Freddo is a local ice cream franchise that does the treat justice.

Of course as the world continues to get smaller, you find American franchises everywhere. In Buenos Aires I saw Burger King, KFC, McDonald's, Starbucks, and TGI Fridays. When I walked past them I noticed they all attracted quite a crowd.

Considering that I have a degree in food engineering and worked directly in the food industry from thirty-one years and indirectly for five and a half it might seem incongruous for me to derive so little pleasure from eating that, with a couple of exceptions, I do it just to survive. Eat to live, that's me. I know two other people only who share my philosophy, and we, the oppressed and misunderstood, are up against the rest of the world, for whom eating is a top priority. Other than for a truly great pizza, which is difficult to find, I wouldn't go out of my way to have a regular meal in a restaurant. I have eaten in restaurants of all kinds all over the world and virtually none has been worth the money to me. Yes, I know I'm missing out on part of a particular location's culture, but, I don't care; I more than make up for the loss in other ways.

Having said that, here's some information about the local water and food.

Online sources said tap water in Buenos Aires is safe to drink. I asked the cabbie who drove me from the airport about this, and in broken English he said brushing teeth with the tap water, yes, drinking, no, as the city water came from the Rio de la Plata, a dirty river, and, though probably microbiologically safe, it tasted chemically. Being cautious, I followed his advice and had no problems.

From what I read and given the high percentage of Argentines with Italian heritage and on the basis of the types of restaurants I saw throughout the city, the locals love pizza. Good for them. It might sound extreme but in continuing my lifelong quest to find the world's greatest pizza, I tried the Buenos Aires version three times. And the city has a world-renowned pizza place: Güerrin Pizza, established 1932. Contrary to what my references warned, it wasn’t too crowded when I got to Güerrin at noon.

My choice for pizza topping is, first, sausage; second, pepperoni; third, sausage and pepperoni; and last, cheese. Strange as it seemed to me, Güerrin—and seemingly all of Buenos Aires—does not offer sausage or pepperoni as options, so cheese—"muzzarella"—it was. I ordered chica size, about twelve-inch diameter, and had no trouble finishing it, even though I didn't care for it. The sauce tasted more appropriate for pasta than for pizza, and the medium-thick crust had some body to it but its flavor was so-so, lacking in character. As with the other two pizzas I had in town, Güerrin's had a lot of cheese, which for me isn’t what pizza is about. Great pizza starts with a great crust followed by great sauce; after that, everything else is just a topping that has nothing to do with the artistry of a pizza. Bottom line for Güerrin: it was a good experience but the pizza was like a grilled cheese sandwich. The bill was AR$500.

Of course Argentina is known for its beef, and I did have a quality steak at a high-end restaurant called El Mirasol, which was on the Puerto Madero riverfront in a renovated group of buildings, convenient to my hotel. The area has several restaurants—almost nothing but restaurants—ranging from fast-food to elegant. El Mirasol, which has been around since 1967, is fancy inside and provides friendly, attentive service. I wanted filet mignon, but it was offered in one size only, 600 grams, about 1.3 pounds—too much for me. The waiter recommended sirloin steak, which clocks in at 300 grams, or about 10.5 ounces—still pretty big, but I was starving, so I ordered that, medium, with boiled potatoes. Hey, my stomach is still Midwestern—plus they didn’t have baked potatoes.

I will say the beef and dessert were outstanding and cost a little less than US$29, including tip. I have to thank the Puerto Rican couple I met on the ship to Uruguay for recommending El Mirasol.

Still not done, the locals love chocolate and ice cream. I tried them both, separately and together a couple of times during my stay and they were flavorful. Freddo is a local ice cream franchise that does the treat justice.

Of course as the world continues to get smaller, you find American franchises everywhere. In Buenos Aires I saw Burger King, KFC, McDonald's, Starbucks, and TGI Fridays. When I walked past them I noticed they all attracted quite a crowd.

The Subway

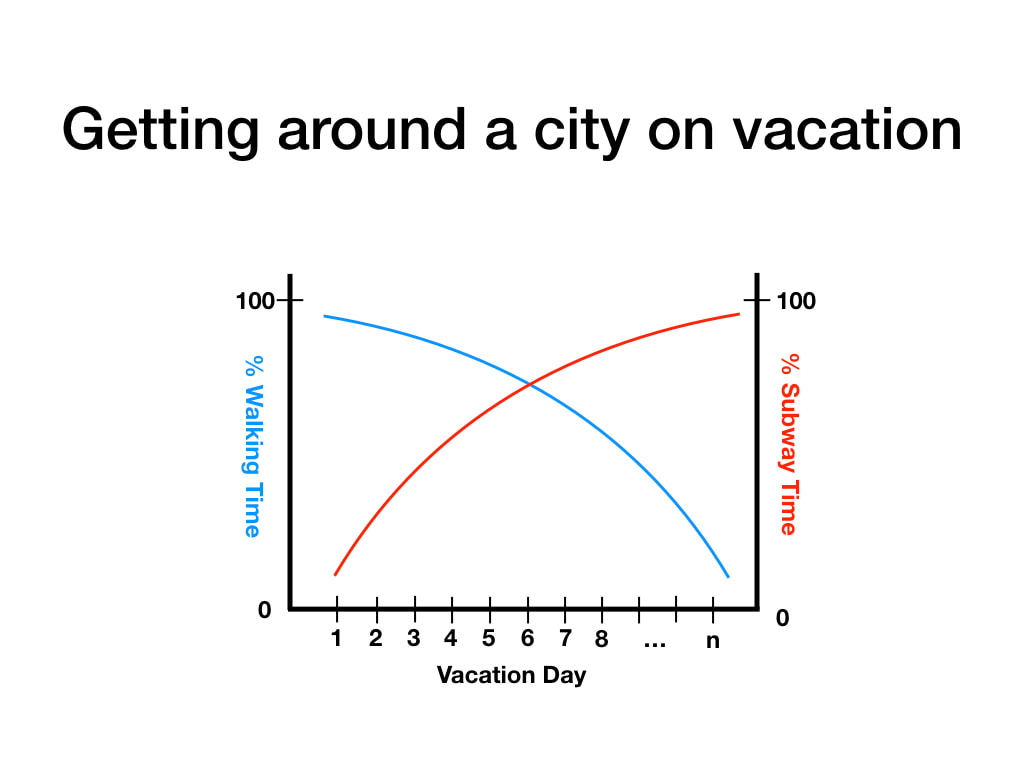

It might seem a little silly to include a section on the subway, but when it's available in a destination I ride it often, so I think a little information now is appropriate. My usual course for urban exploration is lots of walking and little subway at the start of the trip, then lots of subway and less walking by the end of the trip. The graph below shows a simplified ratio of my commuting practices. Subways are so efficient and inexpensive that when your legs need a break, the subway is the best way to go. No, you’re not seeing any sights riding the underground, but you’re not sitting in traffic either, as you would be in a taxi or on a bus.

The Buenos Aires subway is called Subte; I will refer to it as the subway, though, for the rest of this section. The city has six subway lines: A, B, C, D, E, and H and something called the Pre-Metro. I don’t know why there’s no F or G line. Two of the lines travel north and south; the others going, more or less, east and west. The system would be better if it included routes to Belgrano and especially to La Boca.

The subway, opened in 1913, is old and most of it needs remodeling, but, like subways wherever I’ve been, it works well.

On my first full day in country I bought a pass that lasted six days for a mere AR$110; I had to “recharge” the card for my last two days. As far as I could tell, riders don’t have to pay for transfers: once you’re underground you can ride wherever you want on as many lines as you want, with the exception being Line D, at a stop called Diagonal Norte, where you had to show your card again as you passed through the turnstiles.

The subway, opened in 1913, is old and most of it needs remodeling, but, like subways wherever I’ve been, it works well.

On my first full day in country I bought a pass that lasted six days for a mere AR$110; I had to “recharge” the card for my last two days. As far as I could tell, riders don’t have to pay for transfers: once you’re underground you can ride wherever you want on as many lines as you want, with the exception being Line D, at a stop called Diagonal Norte, where you had to show your card again as you passed through the turnstiles.

Geography

By area Argentina is the eighth largest country in the world. Buenos Aires is its capital and its largest city. Forty-eight neighborhoods, or barrios, make up the city, although the main ones, at least for visitors, are those closest to the river. Names for these districts include Barrio Recoleta, Barrio Palermo, Barrio Monserrat, and so on, but the locals drop the barrio when referring to them, as will I for the rest of this webpage.

The defining natural feature of Buenos Aires is the river bordering it on the east, Rio de la Plata. Most but not all geographers define Rio de la Plata as a river, but some say it’s an estuary, bay, or marginal sea. If it is a river, then it is the widest such body of water in the world: 140 miles across at its broadest. Walking along the riverfront, you’re inclined to think you’re next to an ocean, albeit a brown one.

Here are some general information, observations, and experiences about the barrios.

The defining natural feature of Buenos Aires is the river bordering it on the east, Rio de la Plata. Most but not all geographers define Rio de la Plata as a river, but some say it’s an estuary, bay, or marginal sea. If it is a river, then it is the widest such body of water in the world: 140 miles across at its broadest. Walking along the riverfront, you’re inclined to think you’re next to an ocean, albeit a brown one.

Here are some general information, observations, and experiences about the barrios.

- San Telmo was the original settlement in Buenos Aires.

- The boundary between San Nicolás and Montserrat is fuzzy to me and how they fit into Centro and Microcenter even more so. The highlight in San Nicolás is Teatró Colon, Buenos Aires' magnificent opera house. It opened in 1908, and engineers, artists, and patrons alike think it has near-perfect acoustics.

- Belgrano is named for Manuel Belgrano, military leader and creator of the national flag. (I mention him again a little later.) It's an established, wealthy enclave in northwest Buenos Aires. The city's Chinatown is in Belgrano, not far from the second to last subway stop on line D. The website I believed said the shops were open from 09:00 until 21:00. I arrived at 09:15 and most were closed. Not that I would have patronized many, if any, of them anyway, but the energy level on the four-block stretch would have been high had they been opened and the area hustling and bustling, making my time there more enjoyable.

- La Boca is known for the colorful art on many of its buildings. Some of it was fun; some looked like bad graffiti. I walked to La Boca from the hotel, a distance a lot longer than I had interpreted from the map. Ninety minutes of hoofing to get to the Quinquela museum, through some shady parts of the barrio.

- Besides the museum, La Boca is known for Caminito, a “street museum” with lots of vendors, restaurants, and kiosks. The area is colorful and lively—and quite photogenic—but almost everything being peddled was junk for tourists. And the tourists ate it up.

- Not wanting to make the long walk back to Puerto Madero, I asked at the museum for a better way. They recommended bus 152 at the nearby bus stop. I didn’t have to wait long for my ride and was happy when my subway pass worked on the bus.

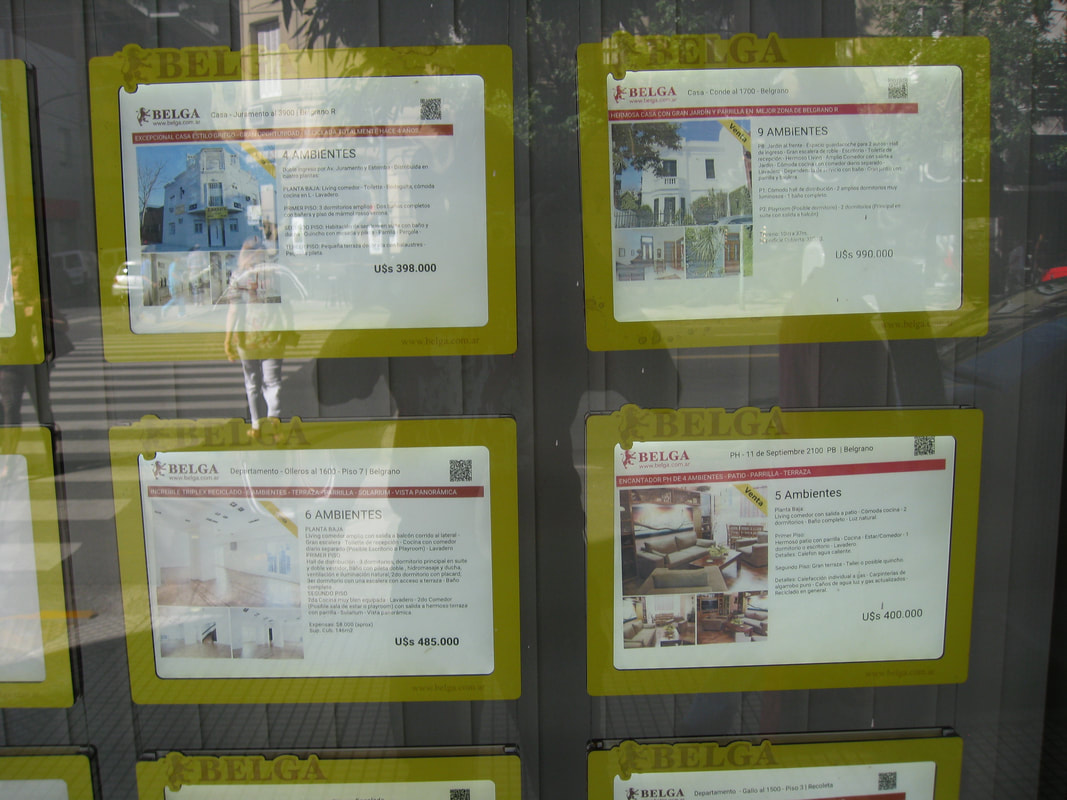

- If there’s one barrio that is Buenos Aires, then it is arguably Recoleta. Affluent Recoleta is replete with gorgeous architecture, history, embassies, mansions, and shopping. And it’s teeming with life and attitude. If you’ve got the money, then it’d be a great place to live in Buenos Aires.

- Recoleta was named for the Récollets, monks of an order today known as the Franciscans.

- The second historical highlight of the barrio is the Church of Nuestra Señora del Pilar. It was built in 1732, making it the second oldest church in the city.

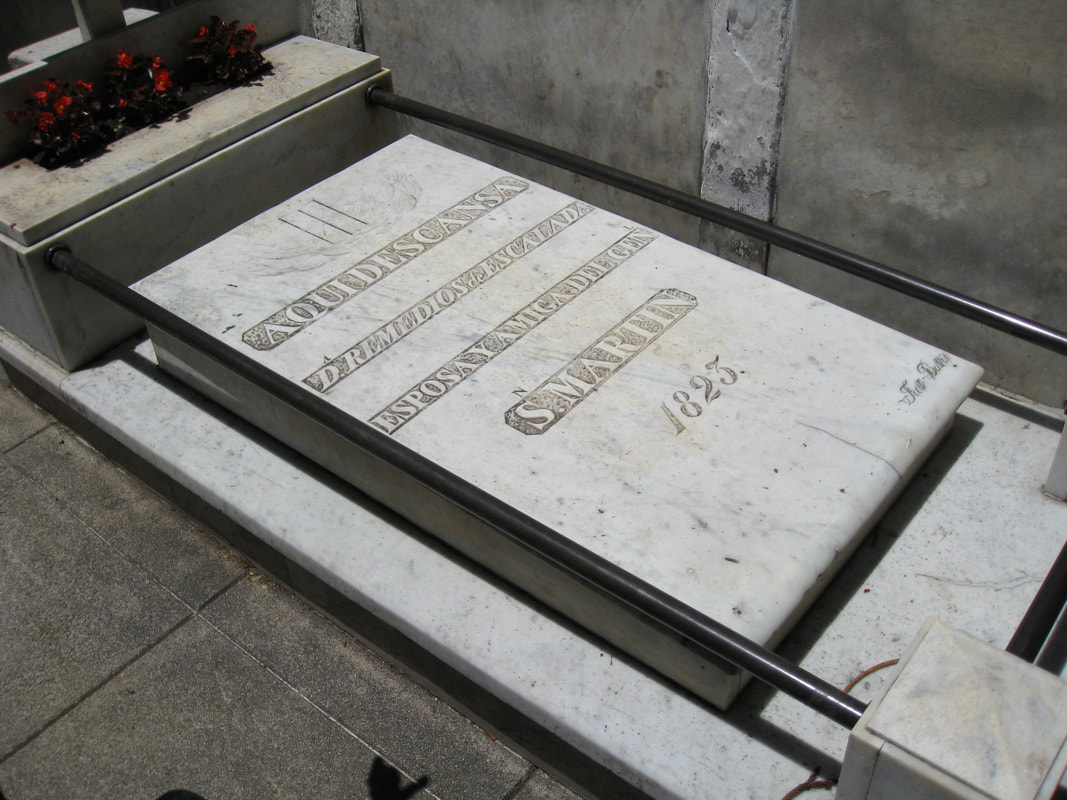

- But probably all visitors to Recoleta come to see the famous graveyard, Cemeterio de la Recoleta. Other than the burial grounds Père Lachaise, Montmartre, and Montparnasse, all in Paris, this is the most famous cemetery in the world. Depending on which source you believe, 6400 vaults and mausoleums are crammed onto fourteen acres of prime real estate, creating an architectural chaos you have to see to believe. The cemetery was part of the Pilar church mentioned above, but it became public in 1822 and the final resting place for many famous Argentines, including Eva Perón, who I discuss in detail later on this page.

- The only other famous person buried here that I knew about before this trip was Luis Firpo, the Argentine boxer who almost was the first Latin American heavyweight champion of the world when, in 1923, he knocked Jack Dempsey out of the ring in the first round of their New York City bout, only to be himself knocked out cold in round two.

- The story of Rufina Cambaceres has to be the saddest tale in the history of mortuary science. Rufina was born in 1883, the daughter of successful Argentine author Eugene Cambaceres. On her nineteenth birthday she learned that her mother was having an affair with her—Rufina’s—fiancé, devastating the young woman and sending her into a cataleptic fit. (Catalepsy is a condition characterized by the body becoming rigid and vital signs being virtually imperceptible.) Her maid called for help, but after arriving the three doctors pronounced her dead. Several days later, at her funeral, her coffin was opened for a last time and workers found her face and the inside of the casket lid covered with scratches. She had been buried alive and had died a second time, suffering a heart attack as she tried to claw her way out of her coffin. Her contrite mother built the mausoleum that’s become a symbol for the cemetery and is arguably its most beautiful. It has a glass front so all can see if Rufina tries to come back again. A marble statue of a young woman stands with its hand on the door, as though ready to open it, if necessary.

- The cemetery is still active, if you will, as some wealthy dead are buried in it today.

- The mausoleums can contain up to fifty coffins, in which case they are placed on shelves or stacked on top of one another, with many being subterranean. Fifty is about the limit as the water table in Buenos Aires is at eighty-two feet (twenty-five meters).

This next grouping of photos is from Recoleta. Most do not have captions.

Streets, Parks, Plazas, and other Infrastructure

Buenos Aires is a planned city, modeled on Paris, inspired by Baron Haussmann. In the mid- to late 1800s, wealthy porteños traveled often to Europe, especially to Paris, returning with fiebre de Paris, or Paris fever, so impressed were they with everything about the French capital that they imported and copied into their city the Parisian flair. In the 1880s, Buenos Aires mayor, Marcelo Torcuato de Alvear, widened some of the boulevards, and like the upper-middle and upper classes, embraced the Art Noveau style that has since become the most recognizable feature of the city.

I have never seen a city that has as many parks and statues as Buenos Aires. I don’t know the number but it seems like after every ten minutes of your walk you see another beautiful green space with a statue. In this section, though, I’ll start first with a couple of miscellaneous facts and then proceed with streets, many of which are named for famous Argentines, for important dates in Argentina’s past, or for countries of the world. The street names and the stories behind them do a great job of telling the history of the city and of the country. Bullet points are the best way to describe the items, as otherwise the short paragraphs would string together without anything connecting them.

Taking it to the streets...

Now for some squares, parks, monuments, and buildings…

I have never seen a city that has as many parks and statues as Buenos Aires. I don’t know the number but it seems like after every ten minutes of your walk you see another beautiful green space with a statue. In this section, though, I’ll start first with a couple of miscellaneous facts and then proceed with streets, many of which are named for famous Argentines, for important dates in Argentina’s past, or for countries of the world. The street names and the stories behind them do a great job of telling the history of the city and of the country. Bullet points are the best way to describe the items, as otherwise the short paragraphs would string together without anything connecting them.

- Most infrastructure in Buenos Aires was done by the British.

- Each block in Buenos Aires is 335 feet by 335 feet (102 meters by 102 meters); all properties have to have a garden in the back.

Taking it to the streets...

- Avenida 9 de Julio. At nearly 460 feet wide (140 meters), over 50% wider than an American football field is long. It’s named in honor of Argentina’s independence day, 9 July 1816, declared after military victories over Spain by soon-to-be national heroes José de San Martín and Manuel Belgrano.

- Calle Florida. It’s been around since 1580 and has had its name changed a couple of times before being designated Florida in honor of an 1814 battle in what is now Bolivia. The local governor changed it again, this time to Peru before it was renamed Florida in 1857. It was Buenos Aires’ first paved street, and, in 1882, the first to be lit with electric lights. This oldest street in the country, starting just north of Plaza de Mayo, Florida is a popular pedestrian mall filled with hawkers trying to change money.

- Avenida Corrientes, one of the main thoroughfares in the city, is Buenos Aires' Broadway. The street is lined with theaters showing musicals and dramatic and comedic plays. (Buenos Aires supposedly has over 280 theaters, a number no city in the world can match.) Corrientes is Spanish for current. It’s also the name of the capital city of an Argentine province.

- Avenida de Mayo is a one-mile stretch of road starting at Plaza de Mayo.

- Avenida del Libertador runs sixteen miles through the city. In 1950, President Juan Perón changed its name from Viceroy Vértiz to honor the aforementioned José de San Martin, liberator of Argentina as well as of Perú and Chile.

- 20 de Septiembre commemorates the 1880 federalization of Buenos Aires, ending an historic problem that caused several civil wars.

- 20 de Diciembre. Two possible events for which the victims of are honored.

- Jorge Rafael Videla was a military dictator in Argentina from 1976–1981. On 20 December 1977 he had one of the founders of the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo thrown from an airplane. The group Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo was formed during the Videla years to find those kidnapped by Videla and later to promote prosecuting those responsible for crimes against humanity.

- December 2001 saw violent anti-government protests across the country, directed specifically at Fernando De la Rúa, president of Argentina from 1999 to 2001. On the twentieth of that month, the protests resulted in thirty-nine deaths, including those of nine minors. It ended with De la Rúa fleeing Casa Rosada in a helicopter.

- Avenida Santa Fe. There are Santa Fes in all Latin American countries, or so it seems. I don’t know the origin of this street’s name, but Carlos, the guide on the walking tour I joined on day two, said Avenida Santa Fe “divides” the city: north of it the city is safer and more sophisticated (his words).

- Autopista 25 de Mayo is the expressway named for the day I described in the History section above.

Now for some squares, parks, monuments, and buildings…

- Plaza de Mayo. I mentioned this in an earlier section. It's the country's oldest public square, having been around in one form or another since 1580. It's named for the start-date of the revolution against Spain on 25 May 1810 and is the site of many of Argentina's most important political events. Among the highlights of this square is the Pirámide de Mayo, the oldest national monument in Buenos Aires, one that celebrates the revolution. Casa Rosada is on the plaza’s eastern border. You can get aboard subway lines A, D, and E at the Plaza de Mayo station.

- Obelisco de Buenos Aires is one of the symbols of Buenos Aires. It’s 221 feet tall (67.5 meters) tall and was unveiled in 1936 as part of the 400th anniversary of Buenos Aries’ founding. It’s in the Plaza de República at the intersection of avenidas Corrientes and 9 de Julio.

- Torre Monumental, formerly known as Tower of the English, but the Argentines changed its name after the 1982 battle for the Malvinas. It was a gift from English immigrants to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the May 1810 revolution. It’s in Plaza del Fuerza Aérea in Retiro and close to Plaza San Martín.

- Parque 3 de Febrero. Named for the Battle of Caseros, 3 February 1852, in which the armed forces of Justo Jose de Urquizo defeated Argentine president Juan Manuel de Rosas and exiled him to England. The new government confiscated his land and ten years later created this park in Palermo.

- Palacio Fernández Anchorena. The Anchorenas were among the outrageously wealthy in nineteenth- and twentieth-century Buenos Aires. Located in Recoleta, it's a mansion the family never lived in and now serves as the Vatican’s embassy in Argentina.

- Basílica del Santísmo Sacramento, in Retiro, was once a private house of worship, commissioned by Mercedes Castellanos de Anchorena, but since 1908 has been part of the Congregation of the Blessed Sacrament.

- The Kavanagh Building was built in 1936 and was for a time, at four hundred feet, the tallest cement building in the world. Local urban legend has it that Corina Kavanagh had it built so her rivals, the aforementioned Anchorenas, could not see their Basílica del Santísmo Sacramento from their palace. Corina was new money and the aristocratic Anchorenas disapproved of her relationship with their son, so the building's location was part of her revenge.

|

|

|

|

Museums and Galleries

I was looking forward to visiting several of the museums and art galleries in Buenos Aires. Great Western cities have great museums, and I was anxious to see what the Argentines had to offer.

My first stop was the Museo Nacional de Bella Artes, or MNBA, on Avenida Libertador in Recoletta. It has an exceptional collection of art not only from Argentina and Latin America, but from Europe and North America, also. You won’t have to look hard to find paintings by Rembrandt, Renoir, Monet, Van Gogh, Rubens, Goya, Pueyerredon, Quinquela Martin, and others. There’s an entire room of Rodin statues. It has a thorough bookstore just off the lobby but whose texts were in Spanish. This is a great museum.

In Palermo is MALBA, the Museo de Arte Latinoamerica de Buenos Aires. An attractive building on Avenida Figueroa, this was practically a gift from local businessman Eduardo Constantini, who donated 220 works from his private collection to the museum. From a schedule I saw in a display case, it looks like MALBA has an exceptional cinema program. While I enjoyed most of the paintings, some of the avant-garde works suspended from the ceiling or sitting on the floor weren’t to my taste, but with its energy and in-your-face attitude, the visitor should not miss this museum.

Also in Palermo is a museum that I had not planned on visiting, but as I was walking right past it one afternoon anyway I decided to have a look. The Museo Nacional de Arte Decorativo is in a beautiful neoclassical building on Avenida Libertador and showcases how the early twentieth-century rich lived in Buenos Aires. I made the circuit in five minutes, not finding the furniture and tapestries interesting.

The acronym MAMBA is how the porteños refer to Museo de Arte Moderno Buenos Aires, in San Telmo. The six-block walk up Avenida San Juan from the Line C subway stop was through a not-so-nice neighborhood. But like most museum buildings, especially art museums, the edifice was impressive, standing out boldly in this barrio. As with MALBA, I liked some of the paintings and a few of the sculptures, but I could not appreciate most of the large three-dimensional forms, the geometric abstractions, or the section on women’s clothing.

Museo Benito Quinquela Martin was a surprise and not on my original agenda. The director of an art gallery I visited in Retiro alerted me to this, and I’m happy he did because this small but excellent museum was a real find. Benito Quinquela Martin was born in La Boca, Buenos Aires, at the end of the nineteenth century. Abandoned as a baby, he was raised in an orphanage before being adopted when he was seven. He started studying art when he was fourteen and started exhibiting his work in 1910, when he was twenty. He died in 1977 and was buried in a coffin he himself painted. Most of the paintings of his I saw were of the waterfront in La Boca and of the people who worked there.

Anyway, the museum had a lot of Martin’s paintings as well as those of other Argentine artists. I loved nearly all of the works. Visitors were allowed to take non-flash pictures in the museum, and I snapped many, as you can see below. But, of course, a small photo can’t capture the beauty of a full-size piece of art.

The Museo Evita, on a side street in Palermo, was on my to-do list, mostly as a curiosity. I knew a little about Maria Eva Duarte Perón from preparing for this trip and from Alan Parker’s 1996 film, Evita, but the extent of my knowledge was slight. (For for the rest of this section I shall refer to Mrs. Duarte Perón by her familiar diminutive, Evita.) This museum, too, was a happy surprise. Originally meant to be a small hotel of French design in the early twentieth century, the structure was purchased in 1923 by a local family, who restored it in Spanish and Italian neo-Renaissance style, including adding a second floor and tower. Evita herself bought the building in 1948 to be a home for women with health, work, or housing problems. It changed hands a couple more times before opening its doors to the public on 26 July 2002—the fiftieth anniversary of Evita’s death—as Museo Evita.

Though not large, the museum is dense and put together with great intelligence and heart. If there’s such an adjective as hagiographical, then that’s how I’d describe it. Walking deliberately from room to room, visitors follow her timeline, starting with her birth in 1919; watch a short video of a segment of her life; and look at photos with descriptions. One room shows clips from the feature films she was in when she was an aspiring actress. Some spaces have examples of her dresses and others have memorabilia from the eponymous foundation she created in 1948. And so you proceed, following her steps as she becomes the second wife to Colonel Juan Perón, then the country’s First Lady when Perón was elected president, and finally to her demise at age thirty-three of uterine cancer. Over two million people lined the streets of Buenos Aires to view her embalmed body lying in state in a coffin with a glass front in the Ministry of Labour Building. Eight devotees were crushed to death in the process. (Perón's first wife, Aurelia, was thirty years old when she died of uterine cancer.)

But the story of the physical Evita does not end with her funeral. (The museum doesn’t cover the following but it's too outrageous not to mention.) When the military overthrew the Perón government in 1955 Evita’s body disappeared. It turned up in Italy in 1971, buried in a crypt in Milan, Italy, under the name María Maggi. That year, Juan Perón, exiled in Spain and living there with his third wife, had the body exhumed and sent to his home, where he kept the corpse in his dining room. To make a long story short, as the cliché goes, Perón returned to Argentina, became president again, died, his wife became president, and she had Evita shipped back to Argentina, where finally, in 1976, Evita was put to rest in the family mausoleum in Cemeterio de la Recoleta. To keep the body secured in Buenos Aires, she’s buried sixteen feet below ground in a crypt supposedly fortified like a nuclear bunker.

As I mentioned in an earlier section, as a visitor I refuse to comment on my host country’s politics. But along the way in preparing for this trip and especially since I’ve been in Argentina, I’ve learned that while half the country loved Evita, the other half hated her—and hated everything associated with the Peróns. (This feeling has softened over time.) I can’t deny I’ve always been fascinated by—and, frankly, infatuated with—accomplished women. During my stay in Buenos Aires my curiosity about Evita piqued and my desire to learn more about her has accelerated. Regardless of what her many detractors have said and continue to say about her—and I will learn more about this, assuming I can find an unbiased biography—Evita was the driving force behind the Argentine suffrage movement, allowing women to vote, in 1951, for a first time. And the foundation she started helped thousands of women and children who were otherwise mired in the despair of poverty in a not yet first-world country.

What’s there to hate about that?

——————--

Walking in Retiro I stumbled on Zubaran el Arte de los Argentinos, a spectacular art gallery that is supposedly the largest in South America, which I assume means by number of paintings and sculptures, not by floor space, though I could be wrong about that. It specializes in Argentine artists. Nestor Paz, chief of sales, was nice enough to spend a lot of time showing me around even though he knew I wasn’t going to buy anything (US$50,000 to US$100,000 are not uncommon prices). Among the artists represented are Benito Quinquela Martín, Justo Lynch, and Daniel Kaplan, the latter influenced by Edward Hopper. Here’s the website if you’d like to see their wares: zurbaran.com.ar.

My first stop was the Museo Nacional de Bella Artes, or MNBA, on Avenida Libertador in Recoletta. It has an exceptional collection of art not only from Argentina and Latin America, but from Europe and North America, also. You won’t have to look hard to find paintings by Rembrandt, Renoir, Monet, Van Gogh, Rubens, Goya, Pueyerredon, Quinquela Martin, and others. There’s an entire room of Rodin statues. It has a thorough bookstore just off the lobby but whose texts were in Spanish. This is a great museum.

In Palermo is MALBA, the Museo de Arte Latinoamerica de Buenos Aires. An attractive building on Avenida Figueroa, this was practically a gift from local businessman Eduardo Constantini, who donated 220 works from his private collection to the museum. From a schedule I saw in a display case, it looks like MALBA has an exceptional cinema program. While I enjoyed most of the paintings, some of the avant-garde works suspended from the ceiling or sitting on the floor weren’t to my taste, but with its energy and in-your-face attitude, the visitor should not miss this museum.

Also in Palermo is a museum that I had not planned on visiting, but as I was walking right past it one afternoon anyway I decided to have a look. The Museo Nacional de Arte Decorativo is in a beautiful neoclassical building on Avenida Libertador and showcases how the early twentieth-century rich lived in Buenos Aires. I made the circuit in five minutes, not finding the furniture and tapestries interesting.

The acronym MAMBA is how the porteños refer to Museo de Arte Moderno Buenos Aires, in San Telmo. The six-block walk up Avenida San Juan from the Line C subway stop was through a not-so-nice neighborhood. But like most museum buildings, especially art museums, the edifice was impressive, standing out boldly in this barrio. As with MALBA, I liked some of the paintings and a few of the sculptures, but I could not appreciate most of the large three-dimensional forms, the geometric abstractions, or the section on women’s clothing.

Museo Benito Quinquela Martin was a surprise and not on my original agenda. The director of an art gallery I visited in Retiro alerted me to this, and I’m happy he did because this small but excellent museum was a real find. Benito Quinquela Martin was born in La Boca, Buenos Aires, at the end of the nineteenth century. Abandoned as a baby, he was raised in an orphanage before being adopted when he was seven. He started studying art when he was fourteen and started exhibiting his work in 1910, when he was twenty. He died in 1977 and was buried in a coffin he himself painted. Most of the paintings of his I saw were of the waterfront in La Boca and of the people who worked there.

Anyway, the museum had a lot of Martin’s paintings as well as those of other Argentine artists. I loved nearly all of the works. Visitors were allowed to take non-flash pictures in the museum, and I snapped many, as you can see below. But, of course, a small photo can’t capture the beauty of a full-size piece of art.

The Museo Evita, on a side street in Palermo, was on my to-do list, mostly as a curiosity. I knew a little about Maria Eva Duarte Perón from preparing for this trip and from Alan Parker’s 1996 film, Evita, but the extent of my knowledge was slight. (For for the rest of this section I shall refer to Mrs. Duarte Perón by her familiar diminutive, Evita.) This museum, too, was a happy surprise. Originally meant to be a small hotel of French design in the early twentieth century, the structure was purchased in 1923 by a local family, who restored it in Spanish and Italian neo-Renaissance style, including adding a second floor and tower. Evita herself bought the building in 1948 to be a home for women with health, work, or housing problems. It changed hands a couple more times before opening its doors to the public on 26 July 2002—the fiftieth anniversary of Evita’s death—as Museo Evita.

Though not large, the museum is dense and put together with great intelligence and heart. If there’s such an adjective as hagiographical, then that’s how I’d describe it. Walking deliberately from room to room, visitors follow her timeline, starting with her birth in 1919; watch a short video of a segment of her life; and look at photos with descriptions. One room shows clips from the feature films she was in when she was an aspiring actress. Some spaces have examples of her dresses and others have memorabilia from the eponymous foundation she created in 1948. And so you proceed, following her steps as she becomes the second wife to Colonel Juan Perón, then the country’s First Lady when Perón was elected president, and finally to her demise at age thirty-three of uterine cancer. Over two million people lined the streets of Buenos Aires to view her embalmed body lying in state in a coffin with a glass front in the Ministry of Labour Building. Eight devotees were crushed to death in the process. (Perón's first wife, Aurelia, was thirty years old when she died of uterine cancer.)

But the story of the physical Evita does not end with her funeral. (The museum doesn’t cover the following but it's too outrageous not to mention.) When the military overthrew the Perón government in 1955 Evita’s body disappeared. It turned up in Italy in 1971, buried in a crypt in Milan, Italy, under the name María Maggi. That year, Juan Perón, exiled in Spain and living there with his third wife, had the body exhumed and sent to his home, where he kept the corpse in his dining room. To make a long story short, as the cliché goes, Perón returned to Argentina, became president again, died, his wife became president, and she had Evita shipped back to Argentina, where finally, in 1976, Evita was put to rest in the family mausoleum in Cemeterio de la Recoleta. To keep the body secured in Buenos Aires, she’s buried sixteen feet below ground in a crypt supposedly fortified like a nuclear bunker.

As I mentioned in an earlier section, as a visitor I refuse to comment on my host country’s politics. But along the way in preparing for this trip and especially since I’ve been in Argentina, I’ve learned that while half the country loved Evita, the other half hated her—and hated everything associated with the Peróns. (This feeling has softened over time.) I can’t deny I’ve always been fascinated by—and, frankly, infatuated with—accomplished women. During my stay in Buenos Aires my curiosity about Evita piqued and my desire to learn more about her has accelerated. Regardless of what her many detractors have said and continue to say about her—and I will learn more about this, assuming I can find an unbiased biography—Evita was the driving force behind the Argentine suffrage movement, allowing women to vote, in 1951, for a first time. And the foundation she started helped thousands of women and children who were otherwise mired in the despair of poverty in a not yet first-world country.

What’s there to hate about that?

——————--

Walking in Retiro I stumbled on Zubaran el Arte de los Argentinos, a spectacular art gallery that is supposedly the largest in South America, which I assume means by number of paintings and sculptures, not by floor space, though I could be wrong about that. It specializes in Argentine artists. Nestor Paz, chief of sales, was nice enough to spend a lot of time showing me around even though he knew I wasn’t going to buy anything (US$50,000 to US$100,000 are not uncommon prices). Among the artists represented are Benito Quinquela Martín, Justo Lynch, and Daniel Kaplan, the latter influenced by Edward Hopper. Here’s the website if you’d like to see their wares: zurbaran.com.ar.

The following are photos I took with natural light of some of the paintings in the Museo Benito Quinquela Martin. The first three are by Martin; the rest are by others whose names I did not record. Click on any one to enlarge it. The last picture in the lower right corner of this grouping is not of a painting but of La Boca from one of the museum's windows.

Movies

For over forty-five years movies have been a significant part of my life. Like most people, I vacation to get a break from the proverbial daily grind. I do activities different from those that keep me busy during the rest of the year. Movies are outside that way of thinking because they’re (usually) a source of pleasure for me, not something I’m trying to get away from. So on vacation I try to see films whenever possible.

In 1985, on a trip to England and Wales, I saw my first movies outside the U.S. The experience was different. For instance, all those thirty-four years ago in a theater in the U.K., before the movie started a woman carrying a tray of snacks, like the vendor at a sporting event, walked up and down the aisle selling popcorn and candy. Way back in 1990, before it became common in the U.S., I selected my seat in the auditorium off a computer screen at theaters in Hong Kong. And so it was, up until a few years ago, when going to the cinema and watching a film in Europe or Asia started mirroring what it was like back home. But for several years those differences provided me a second reason for watching movies on vacation.

Whenever possible—and it occasionally is—I do my best to watch a local film in a particular country, imbuing myself somehow, osmosis or whatever, with the experience in the same way as are the natives. Why, on my first four trips to Korea, where my love for that country started with my loving their movies, I went to the theater and watched Korean films, even though my knowledge of their language is minuscule and I had to follow the story strictly by the images. (Frankly, this is how watching movies began in 1895 and continued for thirty-two years. I ended this practice after that fourth trip there and have stopped doing it altogether in countries whose first language is not English.)

Last, part of the way I prepare for a first or second trip to a country is to watch their films. Easier for some destinations than others, but now living in the digital world I’ve always been able to find some representative of a country’s film industry. Having committed myself decades ago to being a viewer of world cinema, without turning, I hope, into a complete snob, I had already seen several Argentine movies long before I thought about visiting the country. Those I remember having watched are:

La Ciénaga

The Film Critic

The Last Summer of La Boyita

The Motorcycle Diaries

The Mystery of Happiness

The Official Story

The Secret in Their Eyes

Séptimo

(I enjoyed all these except Séptimo.)

I know I’m forgetting one or two, but that’s okay. Now this fall, as I was studying for this trip, I watched the following, all courtesy of Amazon Prime Video and, in one case, iTunes. I’ve included a capsule review should the reader be interested. The number in parenthesis is the year the film was released, presumably in Argentina, according to the Internet Movie Database.

Chinese Take-away (2011)

Mainstream, sentimental but delightful story of a bitter middle-aged hardware store owner in Buenos Aires who inadvertently takes in a Chinese refugee when the latter can’t find his uncle in the big city. Making things more even more interesting, a sweet, lovesick woman has a crush on hardware man. Nothing special in the story of a stranger in a strange land, but great characters in a great location.

City in Heat (2006)

Unremarkable but still worthy look at how three friends react to the suicide of a fourth. Most of the action takes place at a small bar they all used to hang out at in Buenos Aires. A talky character-study.

The Custodian (2006)

No, the title character isn’t cleaning the hallways of the local junior high school. He’s a bodyguard for a political figure of some importance in Buenos Aires. And that’s what the movie is about, the day-to-day activities of a bodyguard. And it’s pretty boring, like the movie. Slice-of-life films I usually enjoy but this one not so much.

Las Mujeres Llegan Tarde (2012)

Strange story of a woman who gives a sailor a boat-load of money after meeting him in a casino—and doing the business with him—and telling him to meet her at an old hotel in a month. The proprietors of the hotel need the money so they….and so on. Intriguing but I can’t say I entirely understood it. Part drama, part thriller, part I don’t know what else.

The Prize (2011)

Autobiographical film about a seven-year-old girl and her mother in 1970s–80s Argentina hiding in a broken-down beach shack from the then military government that might have killed her husband and now might want them. Cinema vérité on steroids, it’s not for everyone and was barely for me.

Truman (2015)

Sky-high recommendation for this story about an Argentine actor living in Madrid and at the tail-end of his journey with terminal lung cancer. His best friend, an Argentine living in Canada, comes to visit him for four days and helps him tie up end-of-life loose ends, including finding a home for his dog, the titular character. Starring ubiquitous Argentine actor Ricardo Darin, this is a great film about friendship, family, and mortality.

Valentin (2002)

It’s late 1960s Buenos Aires and precocious eight-year-old Valentin is living with his paternal grandmother, his parents having divorced, with his mother virtually absent and his father an occasional visitor. We learn about the boy’s life through his narration of the events we watch on the screen, all in flashback. His voice is that of a child’s but his words are those of an adult’s. Charming character study. High recommendation.

Whisky (2004)

A super-slow burn Uruguayan film about a late-middle-aged man, Jacobo, single, presumably never married, who owns a storefront sock factory in Montevideo. On the one-year anniversary of his mother’s death he learns his brother, Herman, from Brazil, is coming to visit him (the brother missed mom's funeral). For reasons we can guess but that the film never explains Jacobo asks an older woman, Marta, who works for him, to pose as his wife while his brother is in town. Marta and Herman seem to make a connection. And so it goes. Little dialogue, still camera, this ain’t for everyone but I thoroughly enjoyed it. This was the thirty-year-old director’s last film. He committed suicide two years after it was completed. “Whisky” was the first film from Uruguay I’ve seen and possibly the last.

White Elephant (2012)

Fathers Julian and Nicolas are long-time friends and priests in Argentina, working in the poorest section of Buenos Aires, after the latter had a horrible experience trying to help people in the jungles of Perú. They’re trying to build a hospital in this slum, in the shadow of a failed hospital project many years earlier. Depressed, Father Nicolas finds his faith weakening and his libido surging in the arms of a beautiful social worker who happens to be a non-believer. Well-made and helpful for my understanding of Buenos Aires.

Wild Tales (2014)

This one is a revelation. The 122-minute film is made up of six vignettes whose general theme is what I can only call entropy. For the characters in each of the short films, everything they do make matters worse, sometimes fatally so. Inventive, energetic, I recommend this one so highly that I can’t find words to express myself.

The Window (2009)

No real story here. Old Antonio is confined to his bed at home, connected to an IV awaiting a visit from his musician son. It’s the last day of his life and he wants to walk once more outside, which proves to be a mistake, as he falls and can’t get up. He’s found by some strangers who help him home. As he dies, back in his bed, he has a vision of his nanny from when he was a small boy. That’s it. A sweet, gentle slice of life.

What was happening cinematically when I was in Buenos Aires? Scouring the internet when I was there these films were playing in the city at some point during my stay:

Hollywood

Addams Family

Charlie’s Angels

Doctor Sleep

Downton Abbey

Ford vs. Ferrari

Frankie

Good Intentions

The Good Liar

Joker

Last Christmas

Maleficent

Midway

Motherless Brooklyn

Project Gemini

A Rainy Day in New York

Ready or Not

Argentina

4 Metros

Las Buenas Intenciones

Lectura Segun Justino

Los Odisea de los Giles

El Patalarga (animation)

Los Somnambulos

Europe

In Safe Hands (France)

Snezhnaya Koroleva Zazerkale (Russia, animation)

Unfortunately, Hollywood is the world's dominant cinematic force, even in Korea, which has, I believe, the strongest market for local movies. The American and European films playing here were subtitled in Spanish; as much as I wish the Argentine ones were subtitled in English, they weren’t, so if I were to attend a showing during my stay it would have to be one of the English-language films.

The only two available films that interested me were Frankie and Downton Abbey. The former was playing at just one theater with just one evening showtime, after nine o’clock, so that was out. And though I had already seen Downton Abbey three times back in Tucson, on a slow Sunday afternoon I decided to see it again.

I went to the multiplex at Recoleta Mall. It has the familiar self-serve kiosks where you select your seat in advance and pay with credit card. The screen was dark when I entered the auditorium, popcorn in hand. Then, at showtime, five commercials, three short trailers less than one minute each, three regular trailers, two advertisement for the theater chain (Cinepolis), one advertisement for the concession stand, and one public service announcement for the theater played, not in this order but seemingly at random. The film started seventeen minutes after the advertised start time—not different from what we have to tolerate in the States.

The multiplex was contemporary by any standard, with a large auditorium and large screen but no reclining chairs. (This is becoming a common feature in U.S. theaters, one I could easily live without.) And, yes, obviously, I loved the film, as did the dozen or so other patrons watching it with me, for they laughed and cried in the expected places.

As an aside, Netflix is apparently popular in Buenos Aires. They advertise throughout the city with posters at bus stops and on the sides of buildings. When I was there they were promoting The Irishman and Stranger Things.

In 1985, on a trip to England and Wales, I saw my first movies outside the U.S. The experience was different. For instance, all those thirty-four years ago in a theater in the U.K., before the movie started a woman carrying a tray of snacks, like the vendor at a sporting event, walked up and down the aisle selling popcorn and candy. Way back in 1990, before it became common in the U.S., I selected my seat in the auditorium off a computer screen at theaters in Hong Kong. And so it was, up until a few years ago, when going to the cinema and watching a film in Europe or Asia started mirroring what it was like back home. But for several years those differences provided me a second reason for watching movies on vacation.